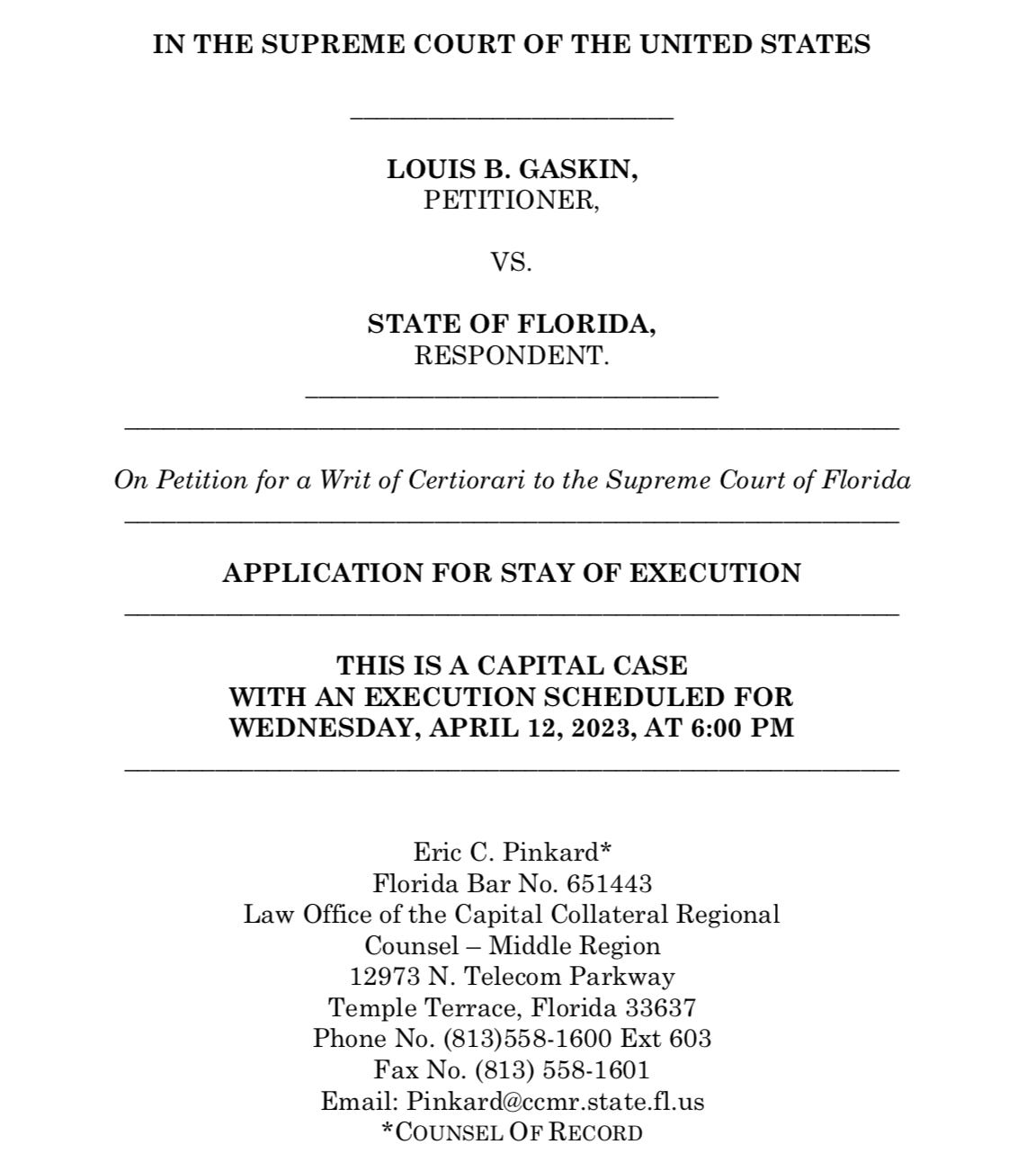

Louis Gaskin filed his cert petition hours after the Florida Supreme Court ruled against him on Thursday. His execution will be on Wednesday at 6 p.m. unless the U.S. Supreme Court grants the application for stay of execution. Our previous posts on Gaskin are here, here, here, and here. For background on Gaskin’s case, please check out this piece from Melanie Kalmanson’s Tracking Florida’s Death Penalty.

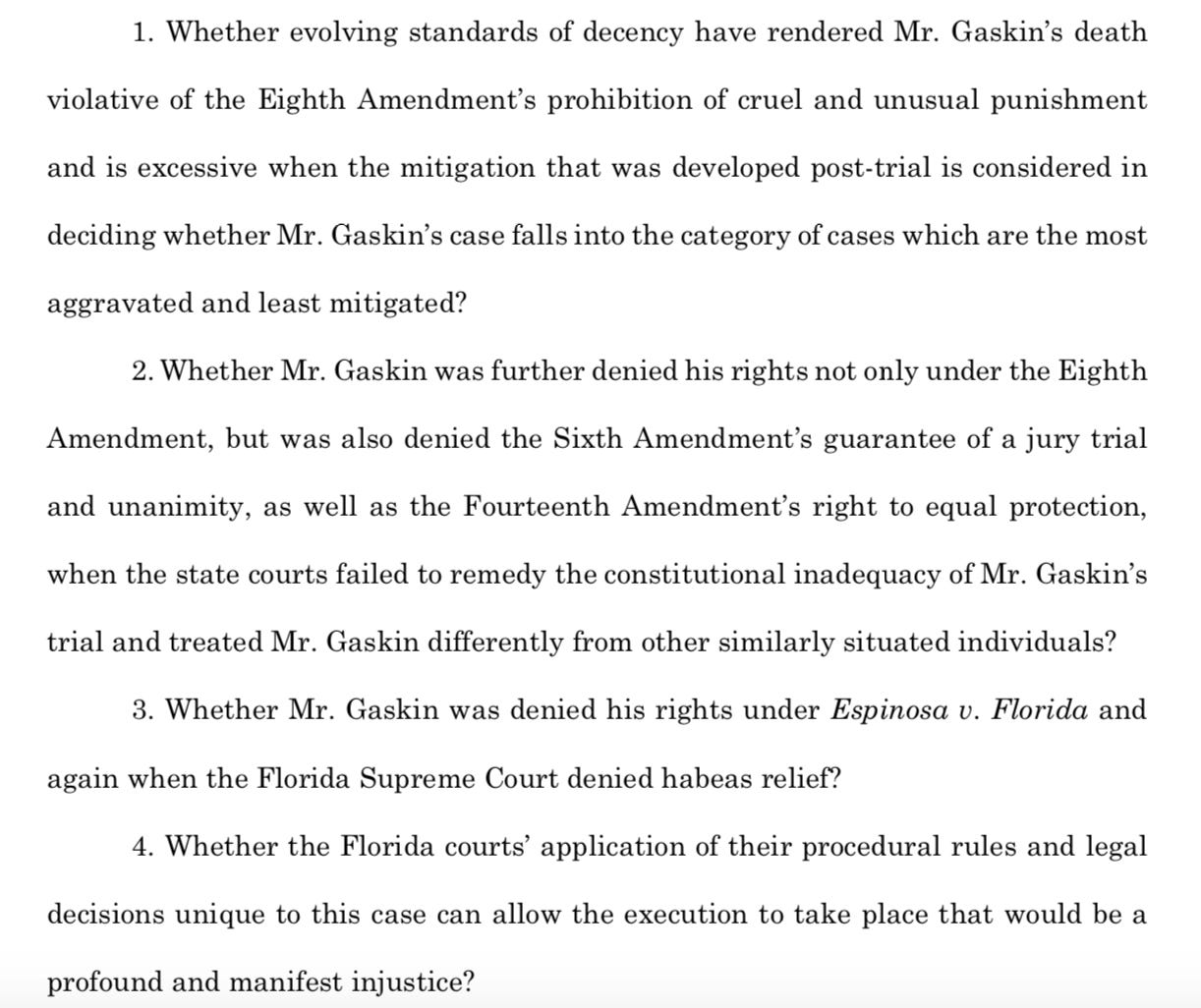

In his petition, Gaskin raises four issues, arguing that his “execution, if it takes place, violates the US Constitution, because the process malfunctioned so completely that his execution would be an intolerable injustice.” The four issues are:

Gaskin first argues that his case is “not one of the most aggravated and least mitigated” because his trial counsel failed to present mitigation evidence to the jury, and despite that failure, four jurors voted against the death penalty. Gaskin claims that “his deprivation, mental illness, and trauma he suffered, was never heard.”

The state’s brief in opposition includes Gaskin’s “very detailed statement about the murders,” in which he described how he repeatedly shot Robert and Georgette Sturmfels and broke into their home. The state argues that this case is among the most aggravated and least mitigated, and that Gaskin’s trial counsel made the strategic decision not to present mitigation, because he was concerned that the mental health testimony would harm Gaskin more than it would help him.

Gaskin responds that the state mischaracterizes his argument as a renewed ineffective assistance of counsel claim. Though “counsel failed,” Gaskin argues that the jury’s “lack of consideration of his mitigation is contrary to the prohibitions against the arbitrary and capricious punishment and his sentence of death is excessive based on well-established constitutional principles.”

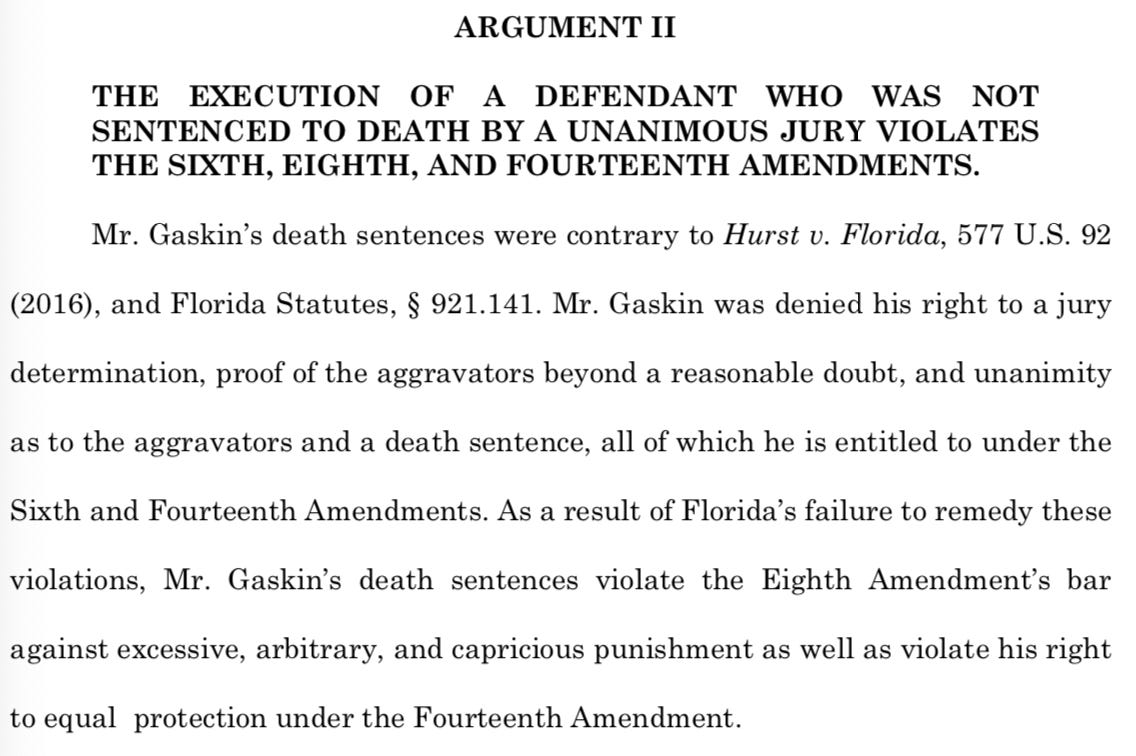

Gaskin’s second argument focuses on Hurst v. Florida, with a few variations.

Gaskin points to the Florida Legislature’s post-Hurst adoption of a new sentencing scheme requiring jury unanimity for death sentences. Had today’s rules applied when Gaskin was sentenced, he wouldn’t be on death row. So Gaskin argues that the signing of his death warrant places him in a “class of one” and that his 8-4 jury recommendation under a now-unconstitutional statute violates the Equal Protection Clause.

As we discussed last week, the Florida Supreme Court didn’t elaborate on the Equal Protection issue, instead finding the argument procedurally barred and pointing to prior cases in which it also didn’t fully analyze the Equal Protection argument but denied relief.

And once again, the state doesn’t engage the Equal Protection argument. In the brief in opposition, the state focuses on retroactivity caselaw in general but doesn’t rebut Gaskin’s Equal Protection claim. In our coverage of the briefing before the Florida Supreme Court, we discussed the state’s focus on the “prior violent felony” and “in the course of a felony” aggravators as part of a harmless error argument while not addressing Gaskin’s Equal Protection claim.

For its part, the U.S. Supreme Court hasn’t intervened in any of Florida’s post-Hurst executions, including several non-unanimous pre-Ring v. Arizona sentences. Former-Justice Breyer explained in his statement respecting denial of certiorari in Reynolds v. Florida that the Florida Supreme Court’s retroactivity caselaw isn’t inconsistent with SCOTUS’s retroactive treatment of Ring in Schriro v. Summerlin, and that Florida was more generous because it applied Hurst to cases on collateral review if the sentence was final after Ring. And Reynolds was before McKinney v. Arizona, in which the majority stated that “Hurst and Ring did not require jury weighing of aggravating and mitigating circumstances” and that “Ring and Hurst do not apply retroactively on collateral review.”

But Gaskin’s claim is different in that he argues Equal Protection based on new legislation, not just that the Florida Supreme Court should’ve applied Hurst to his sentence. Gaskin claims unequal treatment because he’s being denied the right to jury unanimity that all capital defendants in Florida have today. Reynolds wasn’t a warrant case and McKinney wasn’t an Equal Protection case.

Gaskin further argues that unanimity is now the consensus standard for death sentences, so the 8-4 recommendation under the now-unconstitutional sentencing statute violates the “evolving standards of decency” test under the Eighth Amendment. Alternatively, Gaskin argues that “[c]apital sentencing was understood to require a unanimous jury verdict at the time of the Founding.”

These are not pure Hurst arguments, and that’s likely on purpose. Ring and Hurst were Sixth Amendment cases and the Schriro and Asay retroactivity analyses treat the Sixth Amendment jury right as a procedural right, which need not be retroactive. Gaskin will need the Court to focus on his Eighth and Fourteenth Amendment/Equal Protection arguments to prevail on the jury vote issue. If this were a pure Hurst argument, Gaskin would need the Court to distinguish, modify, or overturn Schriro and McKinney.

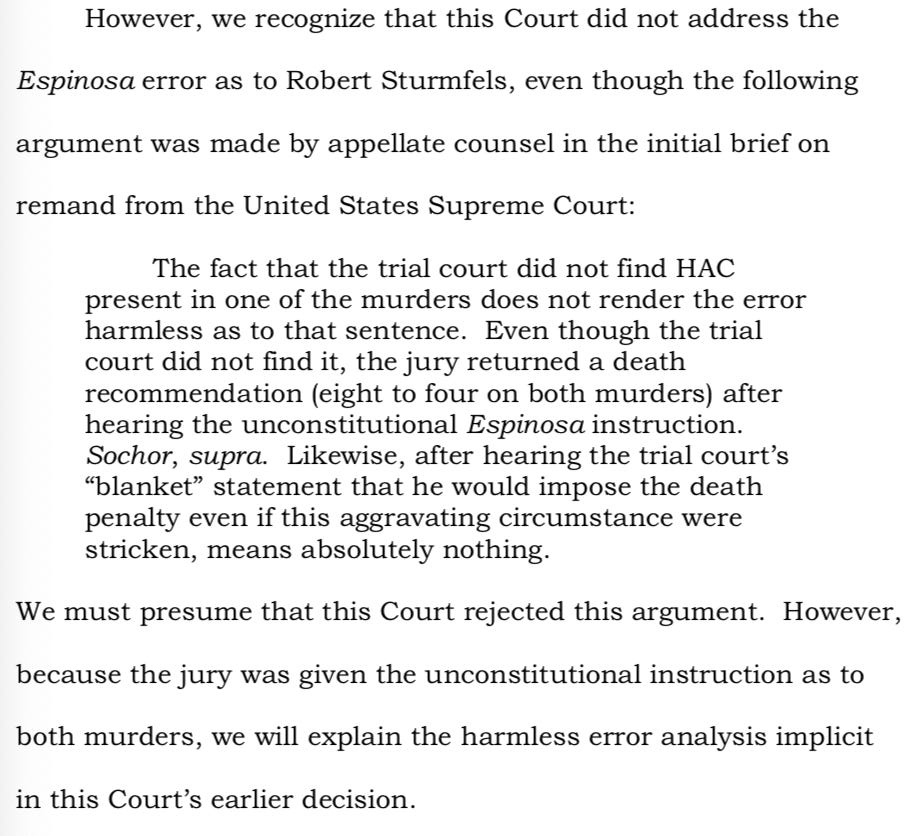

Gaskin’s third claim focuses on the vagueness of the HAC aggravator at the time of his sentence, arguing that the jury instruction violates Espinosa v. Florida. The state counters that the claim is procedurally barred, untimely, and wrong on the merits. The Florida Supreme Court’s discussion of its previous cases was interesting:

Despite the lack of clarity in Gaskin’s previous cases before the Florida Supreme Court, the court held any Espinosa error was harmless.

And Gaskin’s final argument is a frontal attack on the Florida Supreme Court:

The Florida Supreme Court’s recalcitrance in remedying violations of the United States Constitution creates another compelling reason for this Court granting certiorari. The Florida Supreme Court has not fulfilled its responsibility to remedy these constitutional violations when the court clearly could do so.

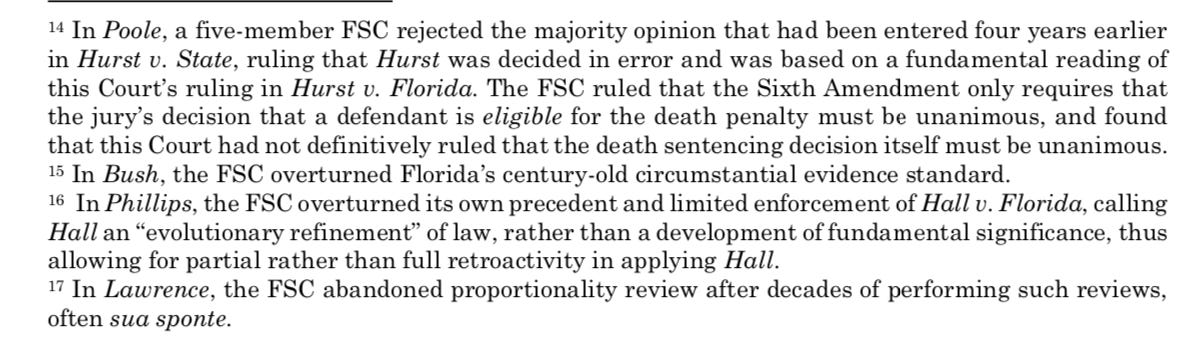

The state argues independent state law grounds prevent Supreme Court review. In the reply brief, Gaskin lists several footnotes of cases in which the Florida Supreme Court recently altered its death penalty caselaw in favor of the state:

Gaskin needs five votes to grant the stay of execution. If he doesn’t get five votes, he will die in Florida State Prison shortly after 6 p.m. on Wednesday.