Louis Gaskin’s briefs are in. He has two cases pending at the Florida Supreme Court—his appeal from the circuit court’s order denying his motion for postconviction relief and his petition for writ of habeas corpus.

Gaskin was sentenced to death for murdering Robert and Georgette Sturmfels. He shot them through the window of their home, then entered, shot them again, and stole various items that he intended to give as gifts. For more background on Gaskin’s litigation history, check out Melanie Kalmanson’s article in Tracking Florida’s Death Penalty.

Gaskin takes on Hurst retroactivity

In the postconviction appeal, Gaskin raises three issues:

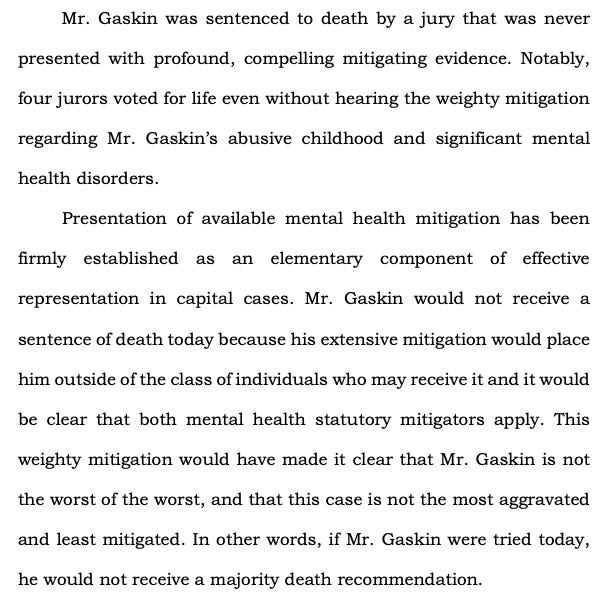

The mitigation evidence outweighs the aggravating factors but his trial counsel presented very little mitigation evidence to the sentencing jury;

The 8-4 jury recommendation of death violates Hurst v. Florida and the Florida Supreme Court’s refusal to apply Hurst retroactively to his sentence violates the Equal Protection Clause in the Fourteenth Amendment; and

31 years in isolation on death row is itself cruel and unusual punishment (also known as a Lackey claim, which we’ve discussed here and on Twitter).

The state’s answer brief argues that the first two claims are procedurally barred (already rejected by the FSC and SCOTUS) and that nobody’s ever had their death sentence reduced on a Lackey claim. And as to the first claim, a previous postconviction court found that Gaskin’s trial counsel made the strategic decision not to present mental health evidence in mitigation because the doctor’s testimony could have hurt Gaskin’s case. Gaskin argues that more mitigation evidence could’ve been enough to persuade a couple jurors to vote for life:

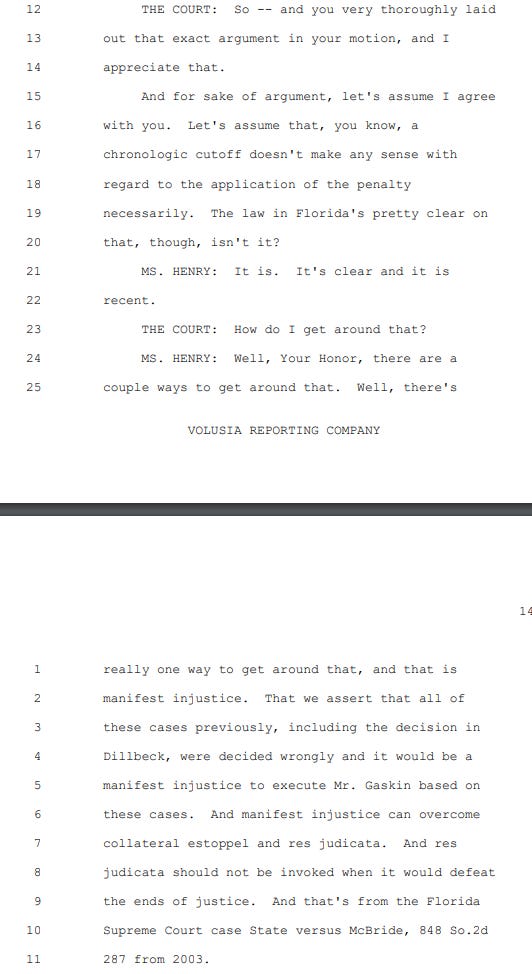

Gaskin’s theme throughout his warrant litigation is that he can overcome procedural obstacles through a showing of “manifest injustice.” Here’s his counsel discussing Hurst retroactivity with the circuit court judge on March 20:

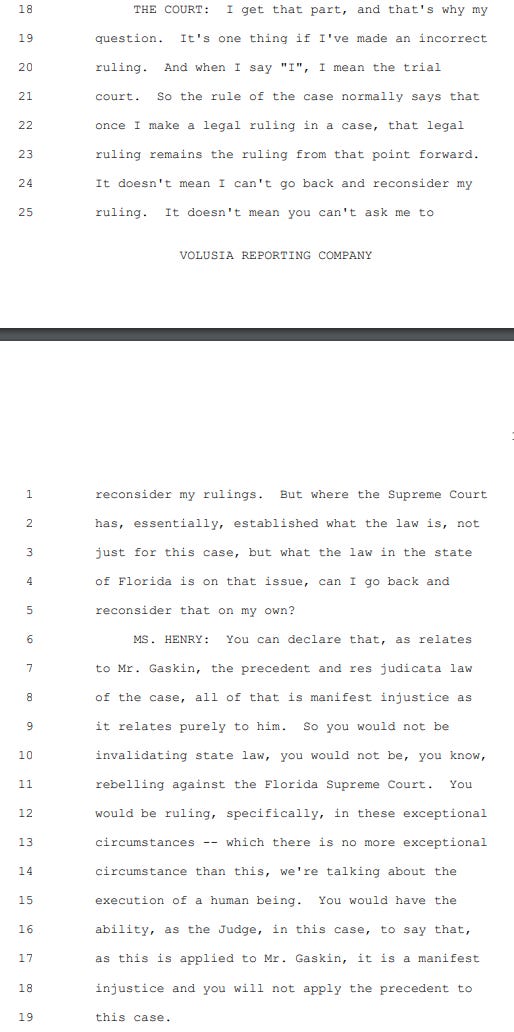

When the court asked how it could find differently than the Florida Supreme Court’s previous rulings, the answer was still “manifest injustice”:

Ultimately, the circuit court didn’t take the “manifest injustice” route and rejected Gaskin’s motion.

Gaskin’s Equal Protection Clause argument about Hurst retroactivity is interesting. The state doesn’t even mention the Equal Protection Clause in its brief, instead arguing that any Hurst error is harmless because the jury’s unanimous verdicts on double murder, armed robbery, and burglary satisfied the “prior violent felony” and “in the course of a felony” aggravators beyond a reasonable doubt. In other words, the jury unanimously found aggravators, so the Sixth Amendment requirements articulated in Hurst were satisfied.

Here’s Gaskin’s initial brief discussing the FSC’s rule that Hurst doesn’t apply to death sentences that were “final” before Ring v. Arizona in June 2002:

Gaskin expands on the Equal Protection argument in the reply brief:

We took a look back to see how the FSC has addressed the Equal Protection challenge to the Ring cutoff.

In Asay V, the court held that Hurst wasn’t retroactive to death sentences that were final before Ring v. Arizona. But the briefing in Asay didn’t address whether the court’s retroactive application of Hurst to death sentences after Ring violated Equal Protection because the FSC hadn’t ruled on that issue yet.

Hitchcock argued that partial retroactivity violated Equal Protection. But the Florida Supreme Court didn’t go through an Equal Protection analysis when it rejected the argument in Hitchcock, opting instead to hold that Asay precluded relief:

But again, Asay didn’t address a Hurst Equal Protection argument. Asay was the first case to go through the lengthy retroactivity analysis for Hurst cases, but not on Equal Protection grounds. And then in Lambrix, the court relied on Hitchcock and Asay in rejecting an Equal Protection attack on the retroactivity rule:

So the court hasn’t provided a robust explanation as to why there’s no relief under the Equal Protection Clause, but it has rejected the argument.

The U.S. Supreme Court hasn’t stopped any execution on Hurst grounds and has declined to consider challenges to Florida’s Ring cutoff.1

In any event, Gaskin will need the FSC to agree with his “manifest injustice” argument to undo its previous ruling that Hurst isn’t retroactive to Gaskin.

Habeas corpus

In the habeas petition, Gaskin argues that his sentencing jury heard an unconstitutional instruction on the HAC aggravator (heinous, atrocious, and cruel). The HAC aggravator at the time of his sentence (then-called “especially wicked, evil, atrocious or cruel”) was later found unconstitutional in Espinosa v. Florida. Gaskin also points out that the sidebar/bench conferences didn’t make it into the trial transcripts.

The state responds with a procedural shot: that Gaskin’s petition violates Rule 3.851 because it was not filed with the initial brief in the postconviction appeal and that habeas petitions are not even contemplated in warrant litigation under the rules. The state calls Gaskin’s petition an attempt to evade the page limits and an “abuse of the writ.” The state also points to the court’s rejection of Gaskin’s Espinosa claim in the early 1990s.

Gaskin’s reply brief takes umbrage with the state’s “abuse of the writ” argument, alleging that the state circumvented page limits in the circuit court proceedings when it filed a 16-page memorandum called “Facts of the Crime and Procedural History,” and then in the response to the postconviction motion’s “procedural history” section, the state wrote that it was relying on its earlier-filed document. This, according to Gaskin’s counsel, was the state “blatantly circumventing the 25-page limitation as laid out in Fla. R. Crim. P. 3.851(e)(3)(B).” And:

On the merits, Gaskin asks the court to reconsider its prior Espinosa ruling in Gaskin’s case. As he argued in the circuit court and in his postconviction appeal, the FSC can undo its prior rulings if it finds a “manifest injustice.” And “[p]rocedural bars must yield to manifest injustice.”

We’ll find out soon if the court takes Gaskin’s invitation to revisit and “correct” its previous rulings. If not, Gaskin will need the U.S. Supreme Court to intervene before April 12 at 6 p.m.

Here’s an archived post from the previous iteration of Florida Court Review discussing Justice Breyer’s statement on the FSC’s retroactivity caselaw. If then-Justice Breyer wasn’t convinced that Hurst should apply to pre-Ring sentences, it’s difficult to see how one gets to 5 votes on the current Supreme Court.

Really great work. Great research finding the Lambrix EPC argument. Obviously, Asay/Hitchcok didn't address those claims. This is the most straightforward I remember this argument being presented.